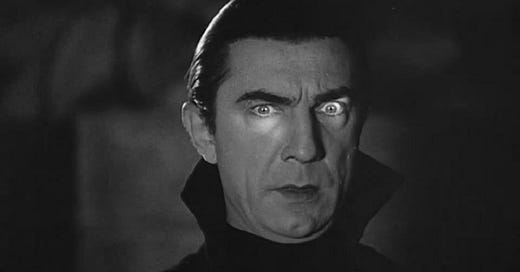

This is the one, of course. The one that established a very particular picture of Dracula in everyone’s head: a man with a long black cloak, a widow’s peak hairdo, and a suave manner allied to a menacing, penetrating stare. Basically, we all think Dracula looks like Bela Lugosi, and that’s because Dracula, in 1931, was Bela Lugosi.

The Lugosi Dracula isn’t particularly similar, physically, to Bram Stoker’s - the biggest difference, which most film adaptations replicate, is that Bela Lugosi doesn’t have a long moustache, which the Count in the book did.

What book Drac did have, though, was that dreadful, mesmerising, terrifying stare, and that’s very much at the centre of Lugosi’s portrayal. To be honest it’s overdone a little: when Dracula is looking to exert his terrible hold over mortals, there’s a close-up of his face gazing silently and intensely at them, and it’s not really as scary as I assume it’s supposed to be. Like all of Lugosi’s performance, it’s really quite hammy, but it’s the ham that’s enjoyable here. I’ve no idea if 1931 audiences were genuinely frightened of Dracula, but you’d think at least some of them were enamoured of the camp value even then.

What Lugosi’s Dracula lacks is the overt sexual energy that later filmmakers have sought to infuse into the character - though that wasn’t really part of Stoker’s vision either. The sexual subtext of vampirism is fairly obvious and will always be present in any version, but Stoker’s Dracula didn’t come on particularly sexy, and Lugosi is much more the old-world gent than the stud.

Dracula of 1931 is not particularly faithful to the book, but it does include some memorable elements of Stoker’s work. One way it scores over Nosferatu in this respect is that, initially at least, one could believe Lugosi’s unnerving-but-superficially-well-mannered Count might convince a fellow to temporarily shelve his doubts and accept his hospitality. God knows how anyone could be expected to take one look at Count Orlok in Nosferatu and not run screaming out of the castle straight away.

There are other treats for fans of the book, like Lugosi’s marvellous intonation of the quote, “Listen to them! Children of the night - what music they make!” It’s the kind of thing that makes one feel that, yes, we’re watching a classic here.

The best bits of this Dracula take place in Castle Dracula in the first act, where Dracula lures and corrupts poor young Renfield (it seems there are a few Dracula movies in which Renfield is the visitor at the beginning, rather than, as in the book, Jonathan Harker, with Renfield already gone mad and obsessively devoted to the Count before the book begins); and scenes at the end in Dracula’s new home in England. This is where the Gothic splendour of the sets, the looming staircases and huge spiderwebs etc are shown to good effect, and where Lugosi prowls the shadows in wonderfully villainous style. There are still moments of silliness, though: where Nosferatu has its striped hyena playing the part of a werewolf, Dracula for some reason has opossums playing rats, and even more inexplicably, an armadillo waddling around in Dracula’s crypt.

(not actually inexplicable, necessarily - apparently it was once thought that armadillos hung around graveyards to feed on human corpses. This doesn’t make it any less ridiculous of course, especially since even if armadillos were cemetery-inclined, finding them in Transylvania would be as weird as…well, as finding an American opossum)

But there’s good silly and bad silly. The armadillo, the opossum, and the hysterically cheap plastic bats that flap around on strings looking like Halloween decorations in Kmart, are among the bad. The good silly includes Dracula’s “I never drink…WINE” line, delivered with such relish by Lugosi, as if he’s restraining the urge to turn to the camera and wink. It’s reasonably absurd to think that Dracula is so eager to constantly hint at his true nature to someone to whom he is ostensibly still disguising himself. But again, that’s part of the fun.

Also enormous fun is Dwight Frye as Renfield. Because of this and his role as Fritz in Frankenstein the same year, Frye was typecast as crazy little freaks, which was a bit of a shame for him, but he was, to be fair, VERY good at being a crazy little freak. And he got to play two iconic roles in two iconic movies in one year, which is more than I’ve ever managed. Anyway, Frye is fantastic, his eyes bugging out, his lips stretching back over his gums to emit that famous lunatic snigger.

When the action moves to London (which in the movie is apparently very close to the Yorkshire town of Whitby, because it’s more convenient for the story and because Americans don’t give a shit where anything in England is in relation to anything else), the whole things gets a bit less engaging. For a start it’s all very stagey - to save money on making a Dracula film, the producers acquired the rights to the successful stage play in which Lugosi was starring, so they could make a small-scale movie mostly set indoors, rather than the Europe-spanning epic that adapting Stoker’s story would’ve entailed. And once we’re in London, the movie looks a lot like a play. A lot of scenes of people talking in the drawing room, as John Harker (not Jonathan), his fiancee Mina, Dr Seward (in this movie the father of Mina rather than the young hero of the book) and Lucy all go through their various tribulations at Dracula’s hand, with a minimum of action.

Frankly, all the heroic characters are, to quote Blackadder, as wet as a fish’s wet bits. Dull and wimpy and deeply uninteresting. The best of them is Van Helsing, played by Edward van Sloan, who wears a funny wig and seeks to match Lugosi in the overacting and comical accent stakes. It’s a battle of wits - sort of - between van Helsing and Dracula, who instead of preying stealthily on his quarry, and evading his pursuers cunningly, keeps popping round to visit them and taunt them with what a big fat vampire he is. Of course he does the preying as well - Lucy cops it in the neck and Mina nearly goes the same way, as in the book. Also as in the book, the heroes - a different and much smaller group than Stoker wrote, admittedly - hunt down and whack Dracula without recourse to beams of sunlight, although in the movie it’s just a chase from one house to the next rather than a gruelling epic journey across Europe and up and down the Carpathian mountains.

I think one thing that is both startling and sort of refreshing, to modern eyes, is just how short Dracula is. They made ‘em shorter in those days, on average, and the film is just 74 minutes from go to whoa. This does have a jolting effect, as you suddenly realise how incredibly fast everything’s moving, compared to what you’re used to in the 21st century. Not that it’s exactly breakneck speed: most of the scenes, in themselves, are positively sedate. It’s just that plot points tumble over each other in a rush, with no lingering - as soon as we’ve established that a thing has happened, it’s on to the next thing, no mucking about. One might say that director Tod Browning could possibly have afforded to let the story breathe a tad more, but one can’t deny there are definite advantages to getting a bloody move on. Mind you, it certainly doesn’t help with one of the movie’s main flaws: the fact that so many of the characters are pretty much total blanks.

Due to the aforementioned staginess and housebound nature of much of the story, a lot of the middle portion of the film plays out a bit like a quaint English murder mystery: van Helsing is like a Dutch Poirot fencing with the murderer - and of course Dracula is a murderer, even if Francis Ford Coppola wouldn’t like to admit it (more on THAT later this week).

For such an iconic movie, one that has had as great an impact on popular culture as anything in the pre-Star Wars era, Dracula doesn’t carry a lot of artistic ambition in it. Much of it is rather staid and conventional, looking and sounding like any other ordinary film of the 1930s. But thanks to the grandeur of the castle scenes, the spectacularly over-the-top performances of Lugosi and Frye (should’ve won an Oscar), and the famous source material that can’t help but draw forth the odd stylistic flourish from Browning, it does stick in the mind, and even more than Nosferatu, a lot of cinematic history will make more sense to you after you’ve seen this most indelible of Draculas.